Social Justice print sponsor AC Law Group in memory of Trevor Davies, the South Sydney Herald’s founding editor and a friend to all in the community. AC Law Group – your criminal lawyers contactable 24/7 on 8815 8167 or visit www.aclawgroup.com.au

____________________________________________________________

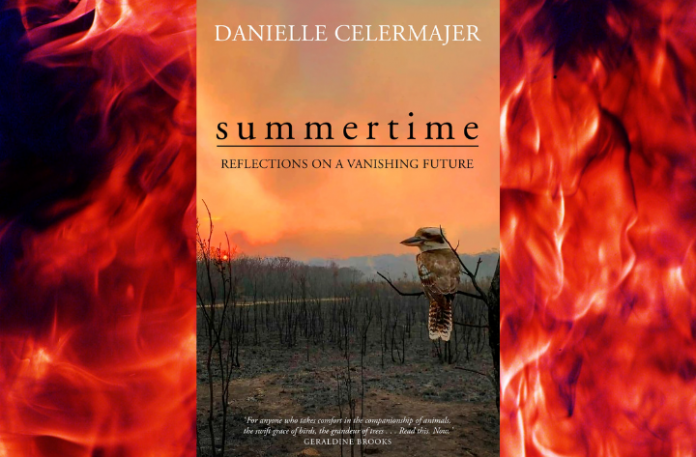

In the crucible of Australia’s Black Summer Danielle Celermajer pondered the personal and broader implications of the climate catastrophe. Her book Summertime: Reflections on a Vanishing Future offers new language and concepts to help us tackle it.

______________

What happened with you and Jimmy the pig during Australia’s Black Summer of 2019-20 that attracted global attention? What was most heartening to you about how people reacted?

We live in a multispecies community, which includes various animals, some of whom experienced terrible violence or neglect. Jimmy and his sister Katy were rescued from the factory farm floor as babies where they had been discarded as “wastage” and they came to us when they were about three. In December 2019, as the fires looked like they were approaching our place, we evacuated all of the “domestic animals” including Jimmy and Katy to what we thought were safer places. Tragically, it was a friend in Cobargo who took them in, and three days later, her place, like so many others, was engulfed in flames, killing Katy. Jimmy survived, but when we brought him home, he was deeply traumatised and also grieving the death of his sister, with whom he had spent every day of his life. as I witnessed his grief, I started to write about what I was seeing.

What drew attention to his story, I believe was the poignancy and starkness of his grief. As humans across the world were feeling terrible loss from the death of so many animals and the destruction of entire ecosystems, his story made apparent that all of these others – the animals themselves – were also grieving. I think people had a sense of this, but Jimmy’s experience and my sharing it gave that intuition form.

I was completely shocked at people’s response. I imagined that people involved in the animal rights movement would respond, but I had no inkling that so many people, all sorts of people, would connect so strongly with his story. He is after all a pig, not a dog or one of the animals we are more accustomed to bringing into our families and communities. I received emails from across the world from people not only wanting to know how he was, but to help – to offer their ideas about healing, or even to send remedies. That the species barrier did not impede this immediate empathy and recognition that here was another being suffering and feeling loss, this gave me a sense of possibility I had not anticipated.

How did Jimmy’s fate and that of his companion Katy stir you to write Summertime, which offers a fresh understanding of how people need to live and interact in a world hurtling towards climate catastrophe?

We were all reeling from the gravity of the Black Summer fires. They outstripped our capacity to imagine what climate catastrophe might look like in our own lives and threw us, into the trauma of the reality of climate change. At the time, many people were writing about the human dimensions of the fires, and in time, people wrote about the death of billions of wild animals. What was missing though was work that conveyed the reality that we humans were not the only ones experiencing and trying to navigate this enormous loss. I wanted to bring others’ experience into our collective stories about what was unfolding. From this initial story, I then realised that I needed to address the larger background problem – that beings other than humans occur to us as resource or material for our use, whereas they too are the centres of their own experience.

Even as we are thinking about technological and political responses to climate change, these dimensions of the solution will only partially address the real problem. That is, as you say, that we interact with all of the other beings with whom we share this earth, and of course also with many other humans, as if they are there to support our aspirations and contribute to our pleasures and profits. I actually believe that many people realise that this is unsustainable and unethical, and even beyond this, that it marks an impoverished way of being human.

In 2019, the climate emergency entered mainstream debates. However, the coronavirus pandemic seems to have eclipsed the urgency for change that was felt in the aftermath of Black Summer. How can we turn people’s attention back to the emergency and prompt them to act collectively to bring change?

In the first instance, it will not be long until new climate events pull our attention. In fact, as I write this, I am flooded in at our place in what is being called a “once in 50- or 100-year storm”. At some point, when these events are yearly or even more frequent – as is already happening – we will no longer be able to resort to these old forms of classification. When a politician says something like this, people will confront them with the truth that is obvious to everyone.

Second, as many people have been doing, we need to draw connections between coronavirus and the climate catastrophe. Scientists have long warned that unsustainable practices around the environment and animals, combined with climate change, will mean a radical increase in the risk of pandemics. These events have a common root.

You cite “humans’ rancorous relationship with the earth and other earth beings” as the soil from which both the fires and the pandemic sprang. “Our incursion into every space, our disruption of every set of relationships, our felt entitlement to extract, construct and belch out what we don’t desire is now the source of the fires making parts of the planet uninhabitable and of the diseases that have crossed over into our own species, ironically rendering us impotent.” (Page 112). What needs to shift in our relationships with the beings you call “more than humans” and the environment to ensure a more equitable future, a more habitable planet, and an end to such broad-scale, human-provoked threats?

The dominant understanding in the west of humans’ relationship with the more than human world is organised around what I think of as the twin pathologies of “exceptionalism” and “extractivism”. According to the first, humans are made of qualitatively different “stuff” to all other beings – we have souls or reason or language or some other quality that makes us superior and (turning to the second) gives us the right to take of all other beings to pursue our own goals. This understanding is not only highly flawed from an ethical point of view. As we are beginning to appreciate, it represents a misunderstanding of how entangled humans are with other beings. This is not an esoteric idea. We are learning that how we feel and our capacity to think is largely shaped by the microbes in our guts. Our capacity to breathe and survive is dependent on trees. Our relationships with the ocean, rivers, mountains are other animals are amongst our greatest pleasures. From this perspective, it is clear that there is no human survival without these other beings also surviving and that whatever form of survival there might be would be impoverished.

Of course, Indigenous peoples have long understood this, and their philosophies and life ways recognise that agency and sentience are not the sole preserve of humans. In this regard, the destruction of environments and the destruction of Indigenous peoples have gone hand in hand, and we need to appreciate that environmental justice and Indigenous justice cannot be separated.

The Black Summer bushfires provided an impetus for you to personally recalibrate. What altered most for you at that point?

I became single minded about the critical importance of building collectives of people primed and poised to act on the climate catastrophe. What was once for me an abstract future became the concrete present. Since then, I have felt driven to do all that I can to wake up those around me – before the fire is in the middle of our shared home, and we watch our world burn.

You are Research Director of the Multispecies Justice Project in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at Sydney University. Can you explain the concept of multispecies justice simply for our audience?

For the most part, our ideas about justice and the institutions we have developed to address injustice have been concerned with human-to-human injustices. At the same time, the fields of environmental justice and animal justice have been growing in recent years. These three have, however, largely remained distinct. But here we are all together, and it seems to us that we need to be thinking about what justice means when we take into account the needs and interests of all people, animals and the environment.

To be clear, we are not saying that what we have decided humans need for justice (to vote for example) also ought to be extended to trees or insects. What different beings require in order to flourish is going to be quite different. Nevertheless, many of our actions and institutions and the changes happening as a result of what humans do have impacts beyond humans, and we rarely take those impacts into account when we are thinking about what is just or right. Think about the impacts of our water policies on the landscapes and animals around the Murray Darling, or land clearing for development in Western Sydney on Koalas. And in turn, think about what mass deforestation means for temperatures in our cities and the lives of all of us.

The important point we are trying to make is that the impacts of our actions and institutions on beings other than humans have been systematically ignored or marginalised. Where they are taken into consideration, they are easily trumped by even trivial human concerns. Taken them seriously means according them the status of claims of justice.

In Summertime you suggest that we are all implicated (albeit unevenly) in causing climate change – all in this together. How can we encourage people to better understand their responsibility for global warming as well as their potential to mitigate it?

In the modern West, we have come to think about responsibility in highly individualised and linear terms, as if we are only responsible for the actions we individually and intentionally take. When it comes to climate change, we can certainly locate actions that individuals have taken for which they ought to be held responsible, like the executives of fossil fuel companies who suppressed information they had decades ago about the climate impacts of their industry, or the media executives and commentators who intentionally undermine science and spread misinformation.

The problem is so much broader than this though. All of us who live within the Global North pursue lives that are dependent on fossil fuel economies. What is so difficult and insidious is that for the most part, it is not when we “do bad things” that we are contributing to the problem, but just when we are going along in our “business as usual” lives – traveling as we do, eating as we do, communicating as we do. Making apparent to ourselves how much of our lives are built around unsustainable and destructive forms of life is critical as a first step. Of course, this type of complicity or indirect contribution is highly unevenly spread – people in the Global North have been the overwhelming beneficiaries of this way of life and often at the expense not only of the earth and other animals but of other humans, Indigenous peoples most of all.

Recognition is not enough though. Everyone needs to be in action; in their own sphere (through their workplace, their school, their community) and then in their role as citizens. Our political representatives need to know that we cannot continue to build infrastructures and economies that are destroying the conditions of life. None of us can solve this individually, but individuals all of have a responsibility to be involved in collective action for radical change. This might sound frightening for people – “radical” is not something everyone feels comfortable with. The alternative though, will be far more radical. And we need to appreciate that what needs to change is radical, in the original meaning of that term – it needs to go to the root of how we live.

An estimated 3 billion animals were destroyed by the fires. To help people grasp the enormity of this loss you say that pausing to hold each of these lives and their relationships in mind would take 950 years; “eleven good human lifetimes doing nothing but contemplating the death of animals by this fire in this country this summertime”. A loss of such magnitude should be intolerable but, clearly, it’s not. And, as you say, “humans are astonishingly adept at getting on with our lives as if we were not, in fact, stumbling on the edge of a precipice”. What will it take to wake us up to the reality of what’s at stake? To the trauma we’re causing?

There are of course many answers to this, being given by many people – like the young climate strikers, artists, and other activists. The quote you gave here is part of my answer. Even as they represent the factual truth, huge numbers and “mega” stories are difficult or impossible for us to grasp. To get to that truth, we also need to tell human sized stories through which humans can connect to this overwhelming change we are living and facing. There is a lot of research telling us that humans can best comprehend injustice and violence and threat when it is delivered to them in the form of individual stories. The problem is that what is happening – what has happened – goes so far beyond individuals. So, I am trying to learn to tell stories that are particular and so graspable, but that then point to this far larger set of questions and challenges.

The House Standing Committee on Environment and Energy recently completed public hearings into Zali Steggall’s Climate Change Bill, which mandates net-zero carbon emissions by 2050, the introduction of low-emission technologies, an independent climate advisory commission and an adaption plan for workers. Overwhelming expert testimony supported the Bill and called on the federal government to take urgent climate action. But the government’s opposition to the Bill makes it unlikely it will be debated in parliament. At what point should people start to use more extreme measures to try to accelerate national action?

This is a question that I think everyone needs to contemplate. What your example shows, however, is that there is an enormous amount that people can do short of more extreme action, If everyone reading this were to join an organisation and also organise with their family and friends and community and contact their representative and tell them that this Bill is the most important action they can take, the political calculus that governments use to make decisions would shift. Australia is a laggard in this regard. Citizens in countries throughout the world have made clear that it is the most important role of their elected governments to act on the climate issue. Our federal government continues to act in the interest of the fossil fuel industry, not in the interest of Australian citizens. We need to make clear that our collective survival is not a partisan issue.

You write about rejecting the “property paradigm” and its toxic entitlement: “My part was to take myself to a place [in rural NSW] where the old conceit could not sustain itself. Where it would not be me working on the earth to make her mine – or even to make me hers – but the earth working on me to make of me, and of us, what she still could.” What has the earth worked within you that you most wish to pass on to others in 2021?

This is a beautiful question. Be present. Be receptive. Notice what is happening to the earth and the beings around you. Notice how much you love and are nourished by rivers or oceans or forests or other animals. Do not be endlessly pulled into distractions from what you are feeling. Yes, you will face fear and grief, perhaps terror and rage. You will though, also feel communion and connection and love. And you will be inside your own life, lived amongst all of these others.

_______________

Summertime: Reflections on a Vanishing Future by Danielle Celermajer (Penguin Random House, $24.99)