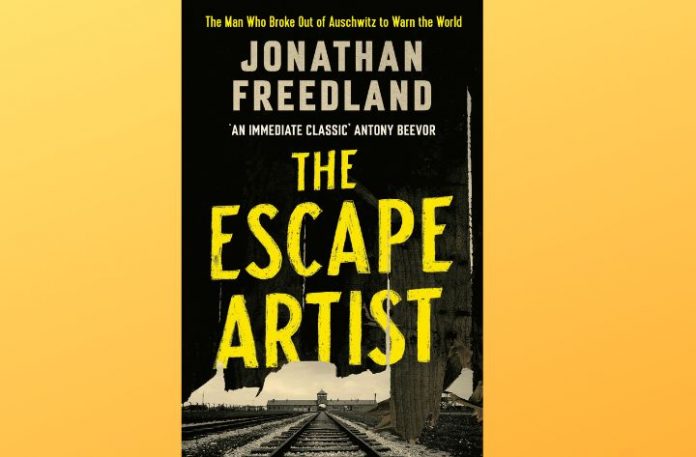

The Escape Artist

Jonathan Freedland

Hachette Australia, $32.99

Rudi Vrba is hardly a household name. Perhaps The Escape Artist, a harrowing, fascinating and meticulously researched book by British journalist and BBC presenter Jonathan Freedland will bring his incredible story to more people; I hope so.

Rudi Vrba (formerly Walter Rosenberg) achieved the near impossible – he escaped Auschwitz. While not the first escapee, he and companion Alfred Wetzler were the first Jewish prisoners to escape and avoid recapture. Their mission was not simply to avoid the gas chambers, but to reveal the horrors of the Nazi camps, hoping that such knowledge would stop, or at least slow, the ruthless killing machine contained therein.

Born in Slovakia, Walter Rosenberg was 18 when, in June of 1942, he was crammed into a cattle car, to emerge in Auschwitz three days later. Within days, he resolved to find a way to escape, though it took two years to perfect and enact his plan.

While more than nine out of 10 new arrivals faced the gas chambers on arrival, Rosenberg was relatively fortunate. He was young and strong; resourceful and multilingual and he found, on occasion, more powerful prisoners willing to protect him.

After a careful study of the camp routine, Rosenberg spied a tiny window of opportunity during which the usually impervious boundary of the camp was less closely guarded. His linguistic ability allowed him to get valuable information from Russian prisoners. By hiding for three seemingly endless days and nights under a woodpile in the camp’s outer ring, Rosenberg and Wetzler managed to escape Auschwitz and traverse occupied Poland to seek a tenuous refuge in Slovakia.

Rosenberg (now renamed Rudolf Vrba) immediately began the almost equally dangerous task of recounting the horrors he had witnessed and committed to memory.

His reasoning was twofold. By revealing to the Allies the horrors of the camps, he hoped to persuade them to bomb strategically, targeting the train tracks leading to them.

In addition, the killing machine only functioned efficiently because the Jews arriving at the camps were exhausted, thirsty, hungry and disoriented. They followed the instructions of the SS, allowing the superbly efficient machinery of death to run smoothly. (On June 27, 1944, 12,500 Jews arrived in Auschwitz from Hungary, nearly all were gassed on arrival.) Vrba hoped to warn Europe’s few remaining Jews about what awaited them, in the hope that any resistance, while individually hopeless, might disrupt the process of mass murder.

The detailed dossier Vrba and Wetzler prepared reached Allied leaders, but did little to change military policy. (The report did help save the lives of many in Budapest’s besieged Jewish community, perhaps as many as 200,000.)

After the war, Vrba was a key witness in numerous war crimes trials and in documenting the Holocaust. His story is important for two reasons: one, in verifying the horrors of the Nazi camps as fewer survivors remain to bear witness and denialism abounds; two, to demonstrate that knowing of atrocities is rarely enough to stop or prevent them.

_______________