A possum-skin cloak covers a bed in a prison cell: the sole comfort in a room stripped of tenderness and care. Onscreen, above the broken toilet, there’s a woman in a cell like this one. Too poor to pay the fine for a minor offence, she’s landed in here. Her arrest and incarceration end in tragedy. She becomes a statistic. Finally, when her death’s investigated, it’s deemed preventable. The sadness of the verdict hangs in the air.

The film moves on to the next woman, and the next, and their stories are hauntingly similar. It’s hard not to feel a little relieved and a lot overwhelmed when it ends.

Typewritten reports stuck to the wall of the cell describe how the police and medical authorities dealt with the women – and the details are distressing. They didn’t follow procedure, they didn’t check, they didn’t notice. Their negligence is clear.

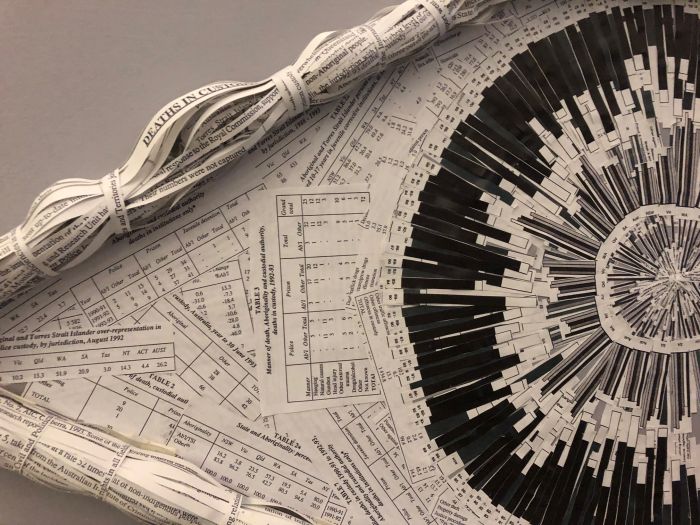

Two artworks in the cell use shredded pages from the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody as their substrate. The deaths they represent are far too many – one death in these circumstances is one too many, after all.

Australia’s criminal justice system is failing our Indigenous people, and the increasing rate of incarceration of our Indigenous women and girls (a rise of 58.6 per cent between 2000 and 2010) is of particular concern.

Ms Dhu is a Yamatji woman who died in custody in 2014. The investigating coroner described her treatment as “inhumane”. Last month Stewart Levitt, the lawyer acting on behalf of Ms Dhu’s family in a human rights complaint with the Human Rights Commission, said “it was more than inhumane” it was “deplorable neglect bordering on commandant treatment as in a concentration camp”.

Professor Chris Cunneen and Dr Amanda Porter, from Jumbunna Research, offer further insights into the death of Indigenous women in detention.

- None of the 11 women who died in custody at the time* of the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody (*1987–1991/RDIAC) could be categorised as a “serious offender”.

- In the majority of cases the “crime” was victimless, non-violent, minor (fine default, offensive language and vagrancy), and what might have been treated as a health issue rather than a criminal problem.

- More than half of these women had been removed from their families as children.

- Nearly all of the recent deaths in detention involving Indigenous women bear resemblance to the circumstances of those women whose deaths were investigated as part of the original RCIADC.

- In 2017 Indigenous women’s imprisonment was more than 20 times the rate of non-Indigenous women, and a large proportion of Indigenous women continue to be incarcerated for minor offences such as fine default.

As chilling as these facts are, the researchers know they’re just part of the picture. “Sometimes the language of statistics and level of analysis used to discuss deaths in custody make us lose sight of something more fundamental. We’re talking about people – people with families and friends, people who loved and were loved, people who died prematurely, often in brutal circumstances.”

At this point in the film, the cell and the cloak come back into the frame. They feature in Sorry for Your Loss, a multisensory art installation at Boomalli Gallery in Leichhardt (May 30 to June 24) driven by Jumbunna Research and Indigenous creatives and academics, Associate Professor Pauline Clague and Professor Larissa Behrendt.

Indigenous women from across Sydney gathered to stitch their art into the panels of the traditional possum-skin cloak in honour of the 48 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women who have died in custody since the announcement of the Royal Commission in 1987.

Professor Behrendt says Sorry for Your Loss aims to “revoice” the women’s stories. She also hopes the cell will travel to communities across Australia and spur dialogue about the ever-growing numbers of Indigenous women being incarcerated.

The project honours precious lives lost, she says, but it also “talks back” to the institutional structures.

“Creativity is an act of defiance, and our cultural practices – like weaving and possum cloth making – are communal. They bring us together to share sovereignty and to exchange stories of resilience, to laugh and form bonds of deep and true affection. These are the things that decolonise and they create a narrative that counters one of oppression, domination and violence.

“Working on this project has helped shape an approach to a human rights issue of critical importance but is also a celebration of the strength of women and the way in which, when we work together, we reweave the fabric of contemporary culture – and that keeps all around us strong.”