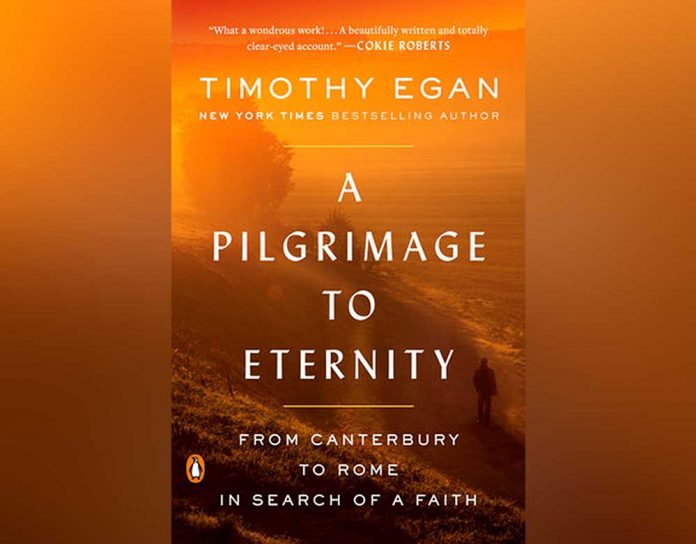

A Pilgrimage to Eternity – from Canterbury to Rome in Search of a Faith

Penguin Random House, $30.75

Timothy Egan

A spiritual seeker, wounded by life’s slings and arrows, goes on an arduous journey. Whether a secular pilgrimage (think Cheryl Strayed in Wild) or a religious one (the 2010 film The Way) the traveller typically dodges danger, nurses blisters and sunburn and is led to deeper faith, self-awareness and inner peace. What, I wondered, could yet another pilgrimage book possibly offer?

Plenty, I discovered, if written by Timothy Egan, a Pulitzer prize winning author of eight previous books and New York Times columnist. Egan’s topics have ranged from bushfires to police corruption to the Depression. A Pilgrimage to Eternity was nominated by the Times as one of its 100 notable books of last year.

Egan, who was raised a Catholic and describes himself as “lapsed but listening”, chooses not the more famous Camino in Spain, but the Via Francigena from Canterbury to Rome. It was described by Sigeric the Serious, archbishop of Canterbury, who walked through Europe to visit the Pope in the year 990.

Purists might disapprove, but Egan doesn’t insist on walking the entire way (1,920 kilometres), instead pledging simply to travel by land; he uses buses, trains and even, for a brief and nerve-wracking stage in Italy, a hire car.

Egan’s book is part travelogue, part memoir, part meditation on the past and future of Christianity and part history of the Church in Europe. He is acutely aware that while he explores sites central to the history of European Christianity, he does so as Christianity steadily wanes on the continent.

An engaging and thorough historian, Egan recounts the events and personalities associated with sites along the Via Francigena. He is struck by how the same institution can be both bloodthirsty and selflessly merciful – reeling at the centuries of church-sanctioned, and often church-ordered, bloodshed. He is in awe of the commitment of Christians in Calais who doggedly feed and clothe asylum seekers, and deeply moved by monastic orders who serve in poverty and simplicity.

We learn that while Egan struggles to embrace the hundreds of miracles attributed to the saints, he is still holding out hope for a miracle in his own life. His beloved sister-in-law Maggie has late-stage cancer, and Egan cannot resist praying for a miracle cure.

Egan ends his pilgrimage a changed person, with “a conviction, this pilgrim’s progress: There is no way. The way is made by walking. I first heard that in Calais … I didn’t understand it until Rome.”

_______________