Where are those happy and edenic times when children were free to make mud pies, decorate them with petal icing and even to taste their produce without arousing the attention of the bacteria police?

Today mothers clean kitchen benches with anti-bacterial “wipes” and the hands of their offspring with “sanitisers”. Childcare centres have a raft of regulations providing a clean, hazard-free, safe environment. Emily Calder’s Cough explores this modern preoccupation with eliminating risks, controlling not only the physical but social environment of children, suggesting that this infectious concern runs the risk of eliminating childhood altogether.

Cough highlights the two main sites of children’s play. The sand pit offers the opportunity for extending, elaborating and excavating, and inevitably involves water (carefully eked out by the centre supervisors). The tree offers the promise of adventure, wonder and the thrill of reaching to the sky. Play, unstructured and spontaneous, is children’s work, as the experts say, and involves the invention of collective fantasies through interaction with other children.

The children’s collective fantasies are represented by young Frank (a very tall Tom Christopherson). His intervention into games is inevitably followed by scary scenarios featuring a monster who lives in a rapidly growing tree or ganging up to torment the most vulnerable. Frank, it seems, is the product of the infectious angst communicated to children through their parents and played out through their imaginative life.

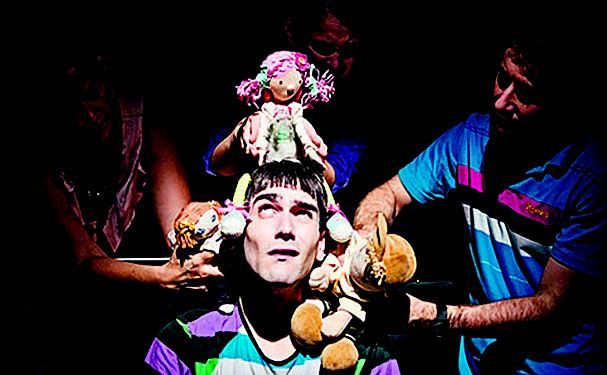

The parents (Melissa Brownlow, Vanessa Cole and Tim Rueben) who also symbolically double as their children (Jess, Isla and Finlay, represented through cloth puppetry) are stressed by their need to be good parents and to have well-balanced children: not overweight, not overactive and not passive. As the children grow “into their own persons” through social interaction the parents become less able to handle the prospect of their loss of control. They demand cleaner sand, the tree cut down, the expulsion of Frank and finally the head of the childcare centre.

The infectious Frank however, has another aspect which is not shown until the close of the play and which perhaps could have been introduced earlier. What we see is horror and ugliness while the beauty and wonder of imagination is under-represented. Although this may suggest that the parents’ overweening concerns deprive their children of wonder and surprise, nevertheless some indication earlier might have balanced the whole.

The director and his production team (Becky-Dee Trevenen/Set and Costume, Tom Hogan/Sound and Benjamin Brockman/Lightning) must be congratulated on the clever staging of a very complex play in a small space with minimal props. The choice of cloth toys was inspired, allowing the rapid and convincing transition from child to adult world and eliminating the rather distracting necessity of having adults act as children.