Sunspots are dark patches on the Sun’s surface, locations where intense magnetic fields – thousands of times stronger than the Earth’s magnetic field – emerge from the solar interior into the Sun’s atmosphere.

Large sunspot groups may be visible with the naked eye on the solar disk if the Sun is observed through thick clouds (you should not observe the Sun with the naked eye, through clouds or otherwise) and the earliest accounts of sunspots date to almost 1,000 BCE.

However, it was only in the 19th century that a semi-regular pattern in the appearance of spots on the Sun was recognised: the solar cycle.

About every 11 years there are many more sunspots on the Sun (a “solar maximum”) and in between (“solar minimum”) the Sun can go hundreds of days without a spot appearing.

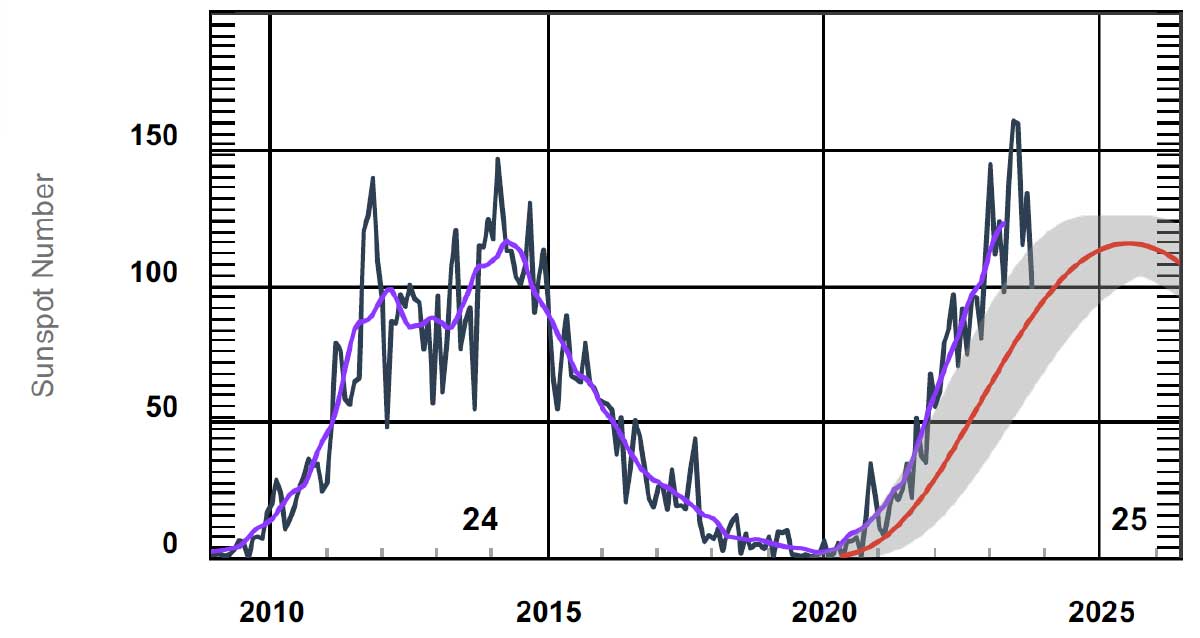

Where are we in the solar cycle? As the figure shows, we’re approaching the maximum of Cycle 25, which should peak during 2025. (The solar cycle numbering starts with Cycle 1, which occurred in the 1760s.)

Data: US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Space Weather Prediction Centre https://www.swpc.noaa.gov/products/solar-cycle-progression

The last solar minimum was around 2019-2020. Cycle 25 is exceeding expectations (a prediction from 2019 is shown in the figure) and the maximum is likely to be larger than the last cycle, but not very unusual for the Sun.

What can we expect with solar maximum? The solar cycle would be of academic interest except that it directly affects the Earth via its influence on space weather – the conditions in our local space environment.

The magnetic fields of sunspots produce “solar activity” – dynamic events in the Sun’s atmosphere. The largest examples of activity are solar flares (enormous magnetic explosions in the Sun’s atmosphere) and coronal mass ejections or CMEs (expulsions of material from the Sun). These events produce enhanced X-ray and extreme-UV fluxes from the Sun, as well as populations of accelerated particles in the Earth’s magnetosphere.

Extreme space weather events can have damaging effects – in the past, large events have disrupted electricity grids, as well as disabling satellites. Space weather storms also produce beautiful auroral displays, down to low latitudes.

The number of flares and CMEs roughly follows the sunspot cycle, so at maximum there are many more of these events. That means there is more chance to see an auroral display, but there is also a small risk of a dangerous space weather event.

Luckily these events are quite rare – the largest event in recorded history was the Carrington event in 1859.

Should we be worried? No, all gauges on the Sun read normal.